So what do those things do for our brain and our body? You've lost 25% of your total sleep, but you may have lost 60, 70, 80% of all of your REM sleep because that's when you're getting your REM sleep in those last morning hours. WALKER: How much sleep have you lost? Well, you've taken away two hours from your eight-hour night of sleep, so you've lost 25% of your sleep. and waking up at 6 a.m., you're going to wake up at 4 a.m. And so instead of going to bed, let's say, at 10 p.m. WALKER: So let's say that, normally, you would sleep eight hours, but today, you want to get a jump start, and you've got an early morning meeting, or you want to get to the gym. Like, what happens when we do skimp on sleep? Because, I mean, we all do it. You can't say, well, I got four or five hours of sleep. And now you have much more rapid eye movement sleep. But as you push through to the second half of the night, that seesaw balance actually shifts.

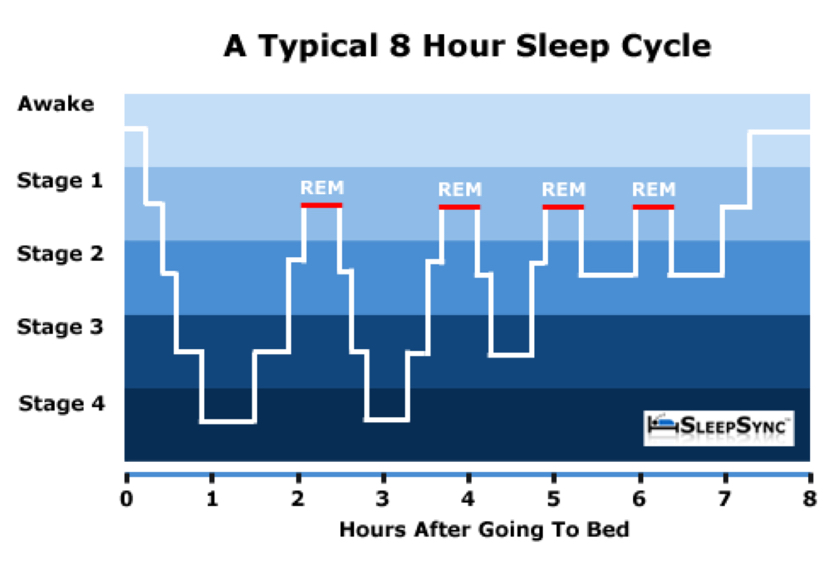

But what changes, however, is the ratio of non-REM to REM within those 90-minute cycles as you move across the night such that in the first half of the night, the majority of those 90-minute cycles are comprised of lots of deep sleep and very little REM sleep. WALKER: Approximately every 90 minutes, you go through a cycle of non-REM to REM. And our brains and bodies need to cycle through both. There's rapid eye movement or REM sleep and non-REM sleep. ZOMORODI: You may have heard of these before. WALKER: When you fall asleep tonight, you're going to experience two main types of sleep.

#Average rem sleep time full#

ZOMORODI: So to understand the strength of a full night's sleep, we need to understand what's happening in our brains, especially during those last few hours before the alarm goes off. And unfortunately, that's what we see with insufficient sleep. And when you lose, the way that it's usually revealed is disease and sickness. You know, when you fight biology, you normally lose. And for us to think, perhaps with a little bit of hubris, that we could come along and start to say, you know, I can train myself to survive on, let's say, just six hours or 6 1/2 hours a night. WALKER: It's taken Mother Nature, let's say, 3.6 million years to put this essential need of seven to nine hours in place for the average adult. ZOMORODI: We humans have evolved to need a specific amount of sleep. Short sleep predicts all-cause mortality. The shorter your sleep, the shorter your life. WALKER: Once you drop below seven hours, we can start to measure objective impairments in your brain and your body. And when we don't make time for sleep, there are consequences. ZOMORODI: That electrical ballet of sleep is crucial for every aspect of our health. It's an electrical ballet that takes place at night.

Your brain is erupting in these incredible bursts of electrical activity going through all of these fantastic sleep stages. You have to give in to sleep and give sleep time to do all of the wonderful things that we know it does. I'll bring it back down to maybe just 50 minutes tonight. I think I'm going to reduce my REM sleep down maybe a little bit. WALKER: You can't just generate sleep, you know, consciously and say, OK, tonight off the menu, I'm going to actually dial up my deep sleep by an hour and a half. ZOMORODI: And Matt says optimizing how your brain works when you sleep - it's not really possible. WALKER: I am a professor of neuroscience and psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, and I'm also the director of the Center for Human Sleep Science here at UC Berkeley. One of the unusual things relative to diet or exercise is that you get to decide, do I exercise and for how long? Do I rush it? Do I not rush it? With sleep, you don't have a choice. And today on the show, we're giving in to things that take time, like sleep.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)